prepared by Katerina Kavanova & Sarka Vasickova //

Sound art is a form of artistic expression where sound serves as the primary medium. While it might seem similar to music at first glance, sound art differs fundamentally in its intention and conceptual framework. Where music typically employs rhythm, melody, and harmony, sound art focuses on the experience of sound itself—inviting us to reconsider our relationship with the acoustic environment and encouraging active listening rather than passive hearing.

What Is Sound Art?

Sound art is an artistic discipline that explores sound more broadly than traditional music. Instead of centering on melody, harmony, and rhythm, it examines sound’s qualities, sources, context, and how listeners experience it.

This practice encompasses diverse approaches, from abstract sonic compositions to site-specific installations created for galleries, museums, public spaces, and digital platforms. Sound artists frequently challenge conventional listening habits and invite audiences to experience sound in fresh, unexpected ways.

The fundamental distinction between sound art and music lies in intention and presentation. Music generally aims to create aesthetic pleasure through organized sound, while sound art often prioritizes conceptual exploration, spatial experience, and the relationships between sound, environment, perception, and meaning. It can reveal ordinarily ignored sounds in daily life or make familiar sounds seem strange by placing them in new contexts.

Sound art also raises profound questions about authorship and collaboration. Many sound artists work directly with communities, incorporating voices, stories, and environmental recordings that belong to specific groups or locations. This collaborative dimension distinguishes sound art from traditional composition, where a single author typically controls all creative decisions. By sharing creative authority or documenting collective experiences, sound artists acknowledge that soundscapes are shaped by multiple forces—social, political, natural, and technological.

Historical Development

The origins of sound art trace back to the early 20th century, when composers and avant-garde artists began questioning the rigid boundaries between music and noise. A pivotal moment arrived in 1913 when Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo published his influential manifesto, The Art of Noises, arguing passionately that industrial sounds and machines deserved integration into artistic practice.

Significant experimental developments occurred during the mid-20th century. Composers working with musique concrète, particularly Pierre Schaeffer, began manipulating recorded sounds using early tape technology in the 1940s. This radical approach treated recorded sound not merely as documentation but as raw material to be shaped, composed, and transformed.

John Cage became essential in expanding the definitions of both music and sound art. His controversial composition 4’33” (1952) challenged audiences to reconsider the nature of sound and silence—the performer remains silent throughout, deliberately focusing attention on ambient environmental sounds naturally filling the space. Cage’s work fundamentally questioned what art and music could encompass.

During the 1960s and 1970s, artists increasingly integrated sound into visual art environments. The Fluxus movement championed these interdisciplinary approaches, while sound sculpture emerged as a distinct medium. Max Neuhaus pioneered sound installations, creating site-specific works that transformed public spaces through carefully crafted acoustic interventions.

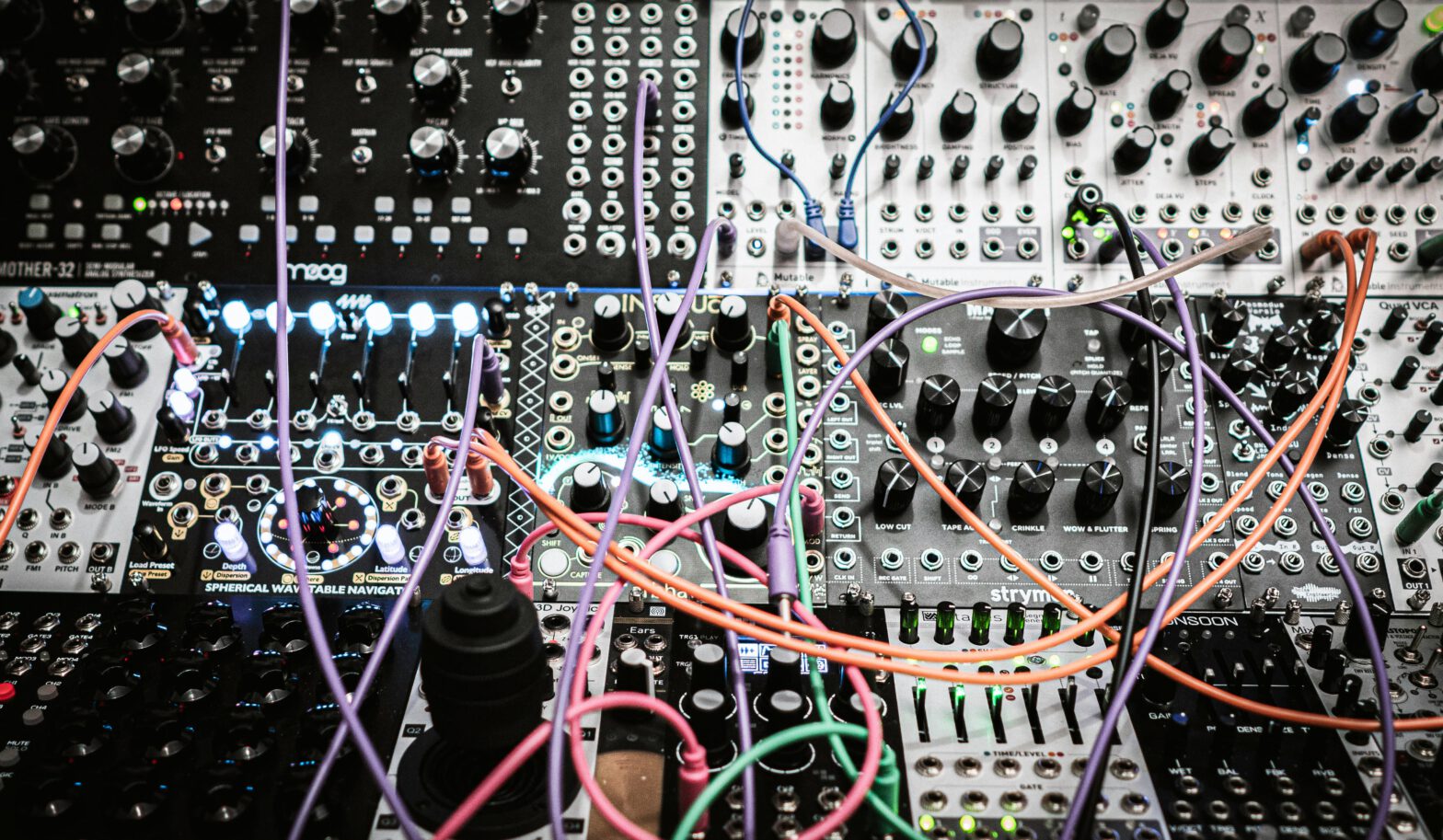

The introduction of electronic music studios, synthesizers, and later personal computers dramatically expanded the creative tools available. This technological evolution continues shaping the field today, with contemporary sound artists working with techniques ranging from analog tape loops to advanced digital programming.

The democratization of technology in recent decades has transformed who can participate in sound art. Affordable recording devices, free software, and online distribution platforms have lowered barriers to entry, enabling artists from diverse backgrounds and geographic locations to contribute to the field. This accessibility has enriched sound art with perspectives previously underrepresented in institutional contexts, bringing attention to marginalized soundscapes and listening practices that challenge Western-centric definitions of art and music.

Categories and Approaches

Sound art encompasses a wide range of creative methods and forms:

Sound-based Composition involves artists utilizing tones, noise, or field recordings to explore fundamental characteristics of sound—its texture, movement, and essence. These works might be abstract or atmospheric, often highlighting qualities like resonance, vibration, or duration.

Sound Installation creates artworks specifically for physical spaces such as galleries, public sites, or architectural environments. In these works, sound becomes a dynamic component of the space itself, interacting with materials, surfaces, and audience movements.

Interactive and Technological Sound Art employs digital tools, sensors, robotics, or custom software to create systems where sound responds to audience actions. This approach transforms listeners from passive observers into active participants.

Site-Specific Sound Art designs works for one specific indoor or outdoor location that cannot be easily relocated without losing meaning. Artists often engage directly with the existing soundscape—whether wind, traffic, water, or human activity—making the location integral to the work.

Found Sounds and Everyday Noise involves using recordings of everyday sounds or recontextualizing them to highlight their musical, rhythmic, or emotional qualities. This approach questions conventional notions of what constitutes “artistic” or “musical” sound.

Sound Sculpture employs physical objects that generate, amplify, or modify sound, existing between visual art and sound art. Examples include outdoor works activated by wind and kinetic pieces featuring motors and resonant materials. Artists construct specialized instruments or sound objects triggered by nature, human interaction, or automated systems.

Field Recording captures environmental sounds that can be presented as-is or incorporated into composed works. This method often carries documentary or ethnographic significance, preserving soundscapes representing specific places, times, or communities. Artists like Hildegard Westerkamp have developed sophisticated techniques for transforming field recordings into rich sonic narratives. This practice also raises questions of representation, listening ethics, and the politics of recording in unfamiliar communities.

Phonography—sound recording as artistic practice—has developed its own aesthetic and discourse. Artists working with field recordings make decisions about context, editing, and presentation. Some share recordings with minimal intervention, while others heavily edit and reshape source material. Online platforms and specialized labels have built communities where artists exchange work and develop shared aesthetic principles.

Performance-based Sound Art consists of live works where artists generate or manipulate sound in real-time. This includes experimental music performances, sound actions, and interventions that blur boundaries between music, performance, and theater. The ephemeral nature emphasizes presence, process, and the unique conditions of each presentation.

Radio Art and Transmission Works utilize broadcasting technologies as artistic media, creating pieces specifically for radio transmission or exploring electromagnetic phenomena creatively. This tradition extends from early experimental radio pieces to contemporary investigations of wireless communication and broadcast infrastructure. These works often invite listeners to experience sound and technology in unexpected ways.

Multimedia Practices frequently combine sound with other forms—visual art, performance, text, or digital media—to create rich, immersive sensory experiences that engage multiple senses simultaneously.

Conceptual Foundations

Several key concepts shape how sound art is created and experienced:

Listening as Active Practice — Sound art often demands close listening rather than casual hearing. Artists employ techniques that help audiences notice usually ignored sounds or hear familiar sounds differently. This attentive listening transforms hearing from passive reception into active engagement. Composer Pauline Oliveros introduced “deep listening,” a practice of listening with complete attention that involves noticing not only sounds themselves but also silences, spaces between sounds, and how the body experiences sound.

Site-Specificity — Many sound works depend fundamentally on their location. Artists consider architectural acoustics, environmental sounds, social context, or site history. Works often change significantly if relocated. Site-specific pieces might enhance natural sounds, introduce new sounds that interact with the environment, or alter how people navigate and experience space.

Temporality — Sound unfolds over time, unlike visual art which exists in space. Sound artists work with duration, rhythm, repetition, and transformation. Pieces can last seconds or extend for hours, days, or years. Temporal structure affects how audiences maintain attention, form memories, and comprehend sonic sequences.

Spatiality — Sound radiates in all directions, and artists use space to shape perception. They can control directionality, distance, reverberation, and movement to create specific effects. Multi-speaker configurations can make sound travel around spaces or emanate from particular points. Understanding how sound reflects, diffracts, and interferes in space is crucial for installation work.

Materiality — While sound itself is invisible, sound art often emphasizes the physical sources that generate or modify it, including instruments, objects, the human body, architecture, and technology. Artists may foreground sound’s physical origins, revealing processes of production or transmission.

Technical Considerations for Beginners

Understanding basic technical concepts enhances both creation and appreciation of sound art. Knowledge of sound behaviour and management provides greater control and enables more interesting, engaging work.

Recording Technologies — Digital tools have made capturing and manipulating sounds more accessible. Learning about microphone types, placement techniques, and recording environment effects is important for quality results. Dynamic microphones are robust and suited for loud sources, condenser microphones are sensitive and capture detail, and contact microphones pick up vibrations directly from surfaces. Recording proximity—close to the source or at distance—affects sonic character. Experimenting with these techniques helps develop desired sounds.

Playback and Spatialization — Playback significantly impacts listener experience. Even simple stereo speakers can create spatial depth, while multi-speaker setups enable sound movement and directionality. Understanding speaker placement, room acoustics, and how surfaces affect sound is crucial for immersive experiences. Sound’s interaction with space can completely transform perception.

Processing and Manipulation — Digital audio workstations (DAWs) enable sound editing, processing, and transformation in numerous ways. You can filter frequencies, time-stretch sounds, layer multiple sounds, or apply effects to create textures and atmospheres. Learning these techniques opens creative possibilities impossible or difficult to achieve with acoustic instruments alone. Experimenting with sound processing helps develop unique styles and discover new sonic possibilities.

Acoustic Principles — Though sound feels invisible, understanding its behavior helps artists make informed choices. Basic concepts include pitch (frequency), loudness (amplitude), resonance (natural amplification), reverberation (spatial echoes), and diffraction (sound bending around objects). Understanding these principles helps predict room behavior, achieve clear recordings, and create interesting interactions between sounds and space.

Tips for Beginners — Start simply and experiment frequently. Try recording everyday sounds, listen carefully to how they change across different spaces, and explore basic processing techniques. Notice how different microphones capture sound and how speaker placement affects experience. Most importantly, trust your ears—learning sound art involves listening, experimenting, and discovering what works for you.

Engaging with Sound Art

For those beginning to explore sound art, several approaches facilitate deeper engagement:

Visit sound installations with sufficient time to fully experience the work. Unlike visual art, which can be apprehended relatively quickly, sound works require sustained attention and often reveal themselves gradually. Allow time for initial orientation, then focus on specific sonic elements, spatial relationships, and your own perceptual responses.

Develop critical listening skills through regular practice. This might involve focused attention to everyday soundscapes, comparing different recordings or sound systems, or analyzing how sound functions across various media.

Explore documentation and recordings of sound works while recognizing their limitations. Recordings cannot fully capture spatial, architectural, or durational aspects of installations, but they provide access to otherwise ephemeral works and historical pieces.

Attend live sound performances and experimental music concerts to experience the immediacy and unpredictability of sound art in action. Live events offer opportunities to witness artists’ creative processes, observe how they manipulate equipment and materials in real-time, and experience the collective energy of an audience engaged in active listening together.

Connect with local sound art communities through workshops, listening groups, or online forums. Many cities host regular sound art gatherings where practitioners share work, discuss techniques, and collaborate on projects. These communities provide supportive environments for learning, experimentation, and constructive feedback that can accelerate your development as both creator and listener.

Conclusion

Sound art represents a vital contemporary artistic practice that expands definitions of both art and music. Its interdisciplinary nature creates rich opportunities for creative exploration and critical engagement, offering accessible entry points while supporting sophisticated conceptual and technical development. Whether you’re listening in a gallery, recording sounds in your neighborhood, or experimenting with digital tools, sound art invites you to hear the world differently. As you engage more deeply with this practice, you’ll discover that sound art is not merely about creating interesting noises or novel listening experiences—it’s about cultivating a more attentive, curious, and critical relationship with the sonic dimensions of existence, transforming how you perceive and navigate the acoustic environments that surround you every day.